Lincoln County supervisor: ‘It all starts on county roads’

Published 4:56 pm Friday, May 8, 2020

- Daily Leader file Photo County roads bear the brunt of transportation in Lincoln County, as well as across the state and nation, yet often have the poorest funding.

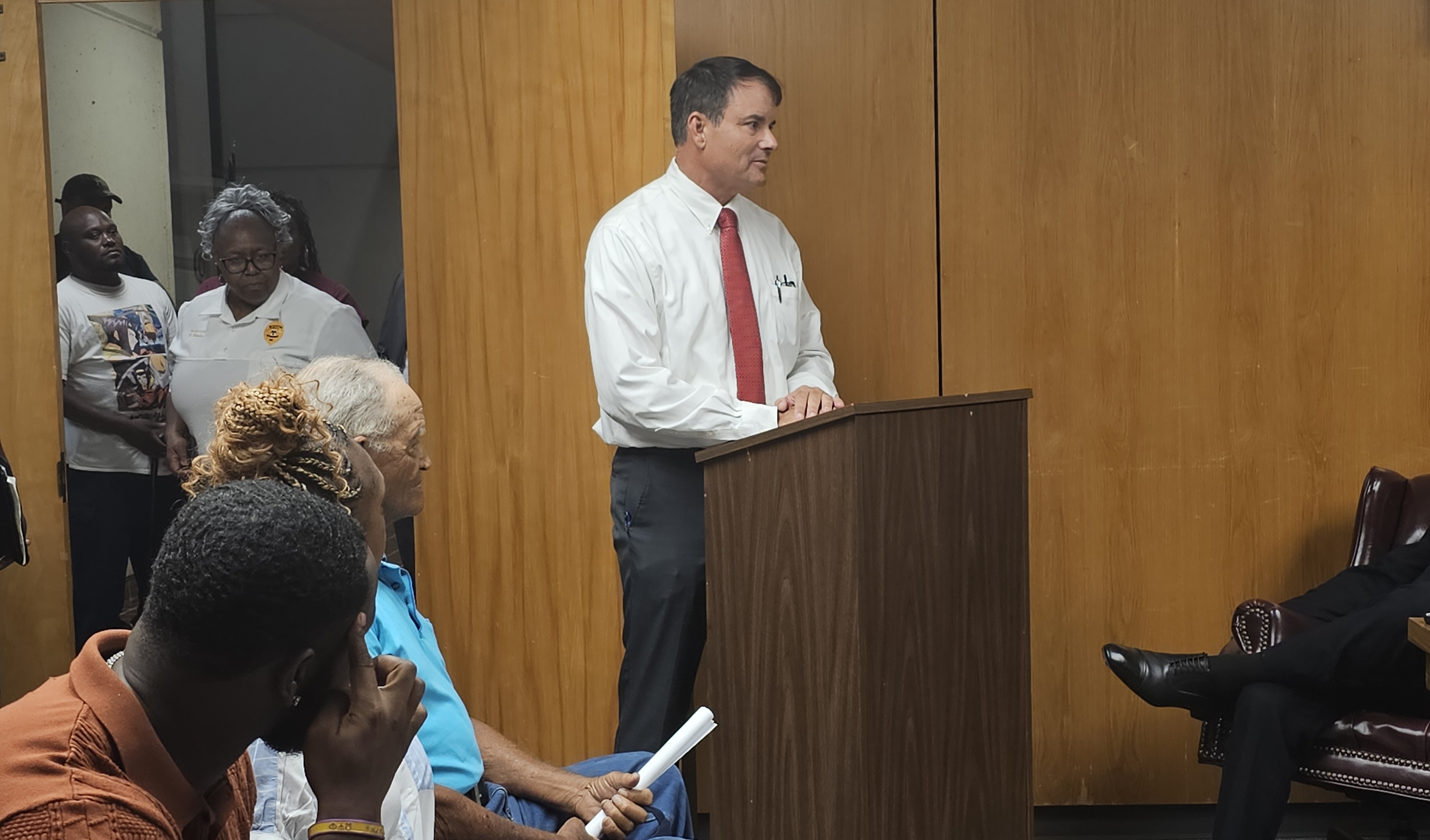

“It all starts on county roads,” says Nolan Williamson, Lincoln County Supervisor District 3.

“Mississippi’s largest industry is agriculture — $7.4 billion,” said Williamson. “Are we investing enough in the infrastructure to support it? The simple answer is no.”

Any time a person’s vehicle hits a pothole or crosses a patch of washboard road, the occupants of that vehicle are certain they’re on some of the worst roads in America.

But where are the worst roads, really?

Mississippi consistently ranks in the top 10 for worst roads in study after study.

Consumer Reports used a four-factor process to determine its list of worst roads in the nation for a report released in 2019 — the dollar amount each state spends per mile of road with data from the U.S. Department of Transportation; total number of fatal motor vehicle crashes with data from the Insurance Institute of Highway Safety; percentage of roads graded poor, fair or good by the Federal Highway Administration; and a survey sampling input from drivers in each state who were given the opportunity to rank their state’s roads from terrible to excellent.

While South Carolina took top prize for worst roads in the nation, Louisiana came in second and Mississippi followed a few steps behind in eighth place. According to FHA data, road repairs account for only 4 percent of the state’s spending — the lowest in the United States. The second-lowest percentage comes from Tennessee, which spends 16 percent of its budget on repairs.

Mississippi has 77,445 miles of roads, spending approximately $21,000 per mile on repairs. Thirty percent of the state’s roads are considered to be in “poor” condition.

Lending Tree compiled information in 2019 from the FHA, as well, ranking each state on three categories: the percentage of roads in poor condition, the number of bridges deemed “structurally deficient” and how much the state spends on road repairs. In this study, Mississippi ranked fourth worst, behind West Virginia, Oklahoma and Rhode Island. Data showed that 11 percent of bridges are structurally deficient and the cost per motorist to travel these roads averages about $820 annually.

The problem for Mississippi lies in funding, according to Mississippi Department of Transportation Executive Director Melinda McGrath.

“The current level of funding means the state-owned rural highway system will continue to be neglected,” McGrath said in 2017. “In order to save Mississippi’s transportation system, action must be taken today. There has been no significant change in state revenue for roads and bridges since 1987. This has caused many Mississippi highways to crumble past the point of repair, and they will now require complete rehabilitation.”

An MDOT press release from the same time stated:

“In the mid-1900s, county roads were given to the state creating a paved network of farm to market routes … Because Mississippi is primarily an agricultural state, these rural corridors are vital to economic development. These roads continue to be neglected, because the majority of today’s state transportation funding goes toward the preservation of major infrastructure routes — interstates and four-lane highways.”

It’s the network of roads that aren’t state-maintained that are foremost on the mind of Supervisor Williamson, however.

Lincoln County’s county-owned and maintained roads were constructed for 37,000-pound load limits, Williamson said. State roads are constructed to an 84,000-pound load limit, and trucks that transport goods over these county- and state-owned roads are rated for 84,000 pounds. That translates into more damage being done repetitively, consistently to county roads that were not built for that much weight.

Current funding allows for only so much repair to those roads, Williamson said, and most of that is a temporary chip and seal repair. Reconstruction requires roads to be closed and rebuilt with asphalt, which can last for five to seven years before needing resealing. Asphalt also costs significantly more than chip and seal repair, and the funding just isn’t there for the counties to keep up with the need.

“We need more funding on different routes,” Williamson said. “Jackson needs to start funding more for asphalt.”

The only local source to fund road improvements comes from increases in land taxes, and most of the county’s budget goes elsewhere. In most counties, the criminal and court systems’ expenses account for more than 50 percent of the general fund. For Lincoln County, that amount is 60.37 percent, Williamson said, with only 24.83 percent of the total budget spent on infrastructure.

“Many believe counties have an endless pool of money to improve roads. In reality, the funds they receive barely cover general maintenance,” he said. “Very little money is available after general maintenance and personnel costs. If inadequate funding isn’t reversed, the county transportation system will completely fail.”