A stigma like no other

Published 4:24 pm Tuesday, May 5, 2020

Writer’s Note: If any word has made a resurgence lately, it’s “quarantine.” But the truth is, whether used as a noun or as a verb, it’s really no stranger to the American vocabulary. This column is the third in a series related to a quarantine in our sister state that lasted nearly half a century.

Misconceptions about leprosy, known now as Hansen’s disease, were understandable in the past, but not these days. Nearly 80 years have passed since researchers at the national leprosarium in Carville, Louisiana, discovered an antibiotic triumvirate — dapsone, rifampin and clofazimine — could halt the disease and render those infected non-contagious. While the effects of leprosy may be chronic, the disease itself is not a life-long condition. Bottom line: Once leprosy is treated, it’s part of a patient’s medical history.

Repeating that refrain has in recent years help a lawyer from New Orleans take his diagnosis in stride, and a young man from India break the news to his fiancée. After all, they only “bumped into some bacteria,” as their counselor puts it.

But leprosy is a disease with ancient implications. Even in a culture that rejects the teachings of the Bible, its references to leprosy — sidled up to words like cursed, outcast and unclean — are well-known. The question is, do they mean the same thing now?

Bill Simmons says no. When he took the reins at American Leprosy Missions’ Greenville, South Carolina, headquarters nine years ago, he studied books in the Bible like Leviticus and 2 Kings for clarification. He soon recognized that everything hinged on the meaning of the Hebrew word “zaraath.”

“Hansen’s disease just doesn’t mesh with the conditions described in the Old Testament,” he says. “Our patients don’t become white as snow, and their hair doesn’t turn white. Hansen’s disease doesn’t affect garments or walls of houses.”

While the New Testament focuses on healing leprosy rather than listing its symptoms, it uses the Greek word lepra to identify the malady. Simmons says it’s too bad Norwegian researcher Gerhard Hansen borrowed the term when in 1873 he named his bacillus M. leprae. Its microbes manufacture peripheral nerve-damaging Hansen’s disease, not the ancient variety of ailments known as leprosy.

Even so, Simmons stresses that Jesus wasn’t focused on what type of bacteria people had: “He was concerned that people were excluded.”

Exclusion is an assault on human dignity, the imago Dei. In the past, some governments operated on limited knowledge of M. leprae’s capabilities, and they’ve paid for being overprotective. A Japanese court last year ordered the state to compensate relatives of leprosy patients it quarantined. Here in the United States, officials promised lifelong care to former patients it detained at Carville. Fifteen are still living, and 14 receive an annual $52,275 stipend. Eight come to Baton Rouge for treatment — not for leprosy, but for its lasting effects.

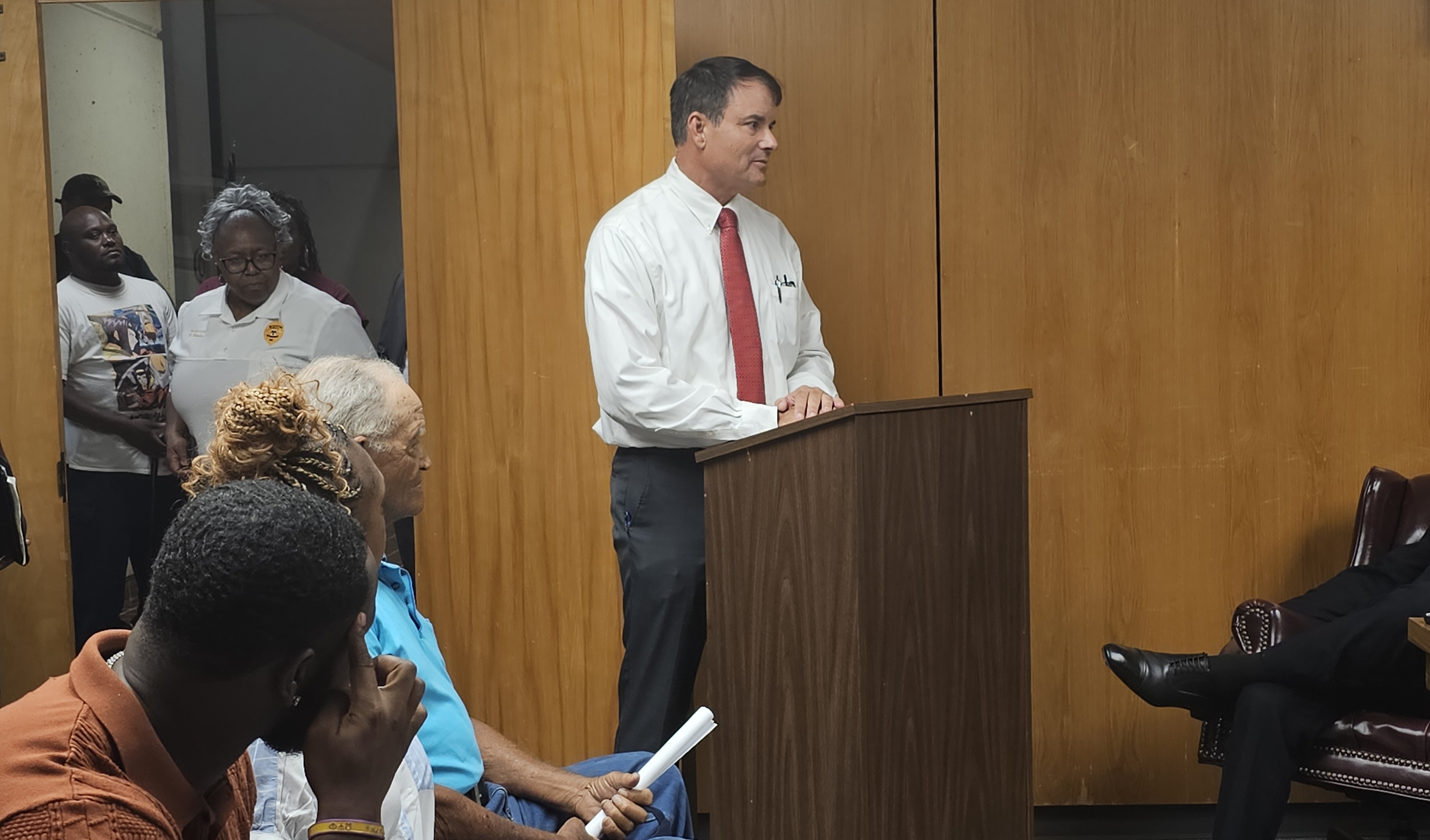

National Hansen’s Disease Programs Director Kevin Tracy is a captain with the Public Health Service. He’s the kind of guy who measures his words and checks them twice, especially when discussing money. Tracy doesn’t believe the size of his program’s budget is related to righting wrongs, but he admits the stigma attached to leprosy has financial leverage: “Our funding has downsized through the years, but there’s always a vocal outcry when further reductions are proposed. When our budget was cut in 2018, congressional inquiries motivated by public response reduced the cut from $3.6 million to $1.5 million.”

Long range, Tracy says he stands on the side of eradication. And if leprosy can one day be eradicated, maybe its stigma can, too.

Back at the National Hansen’s Disease Clinical Center in Baton Rouge, that’s what patients are hoping. The same goes for nurse practitioner Amy Flynn. When she took the job as clinic manager last year, she wondered what her teenagers would think about their mom working around leprosy.

“I don’t know if it’s necessarily generational, but I explained all about it to both my kids, and nothing. Not even any questions.” She pauses. “There’s a lot of hope in that.”

Kim Henderson is a freelance writer. Contact her at kimhenderson319@gmail.com. Follow her on twitter at @kimhenderson319.