Funeral at Shiloh

Published 9:00 am Friday, April 11, 2025

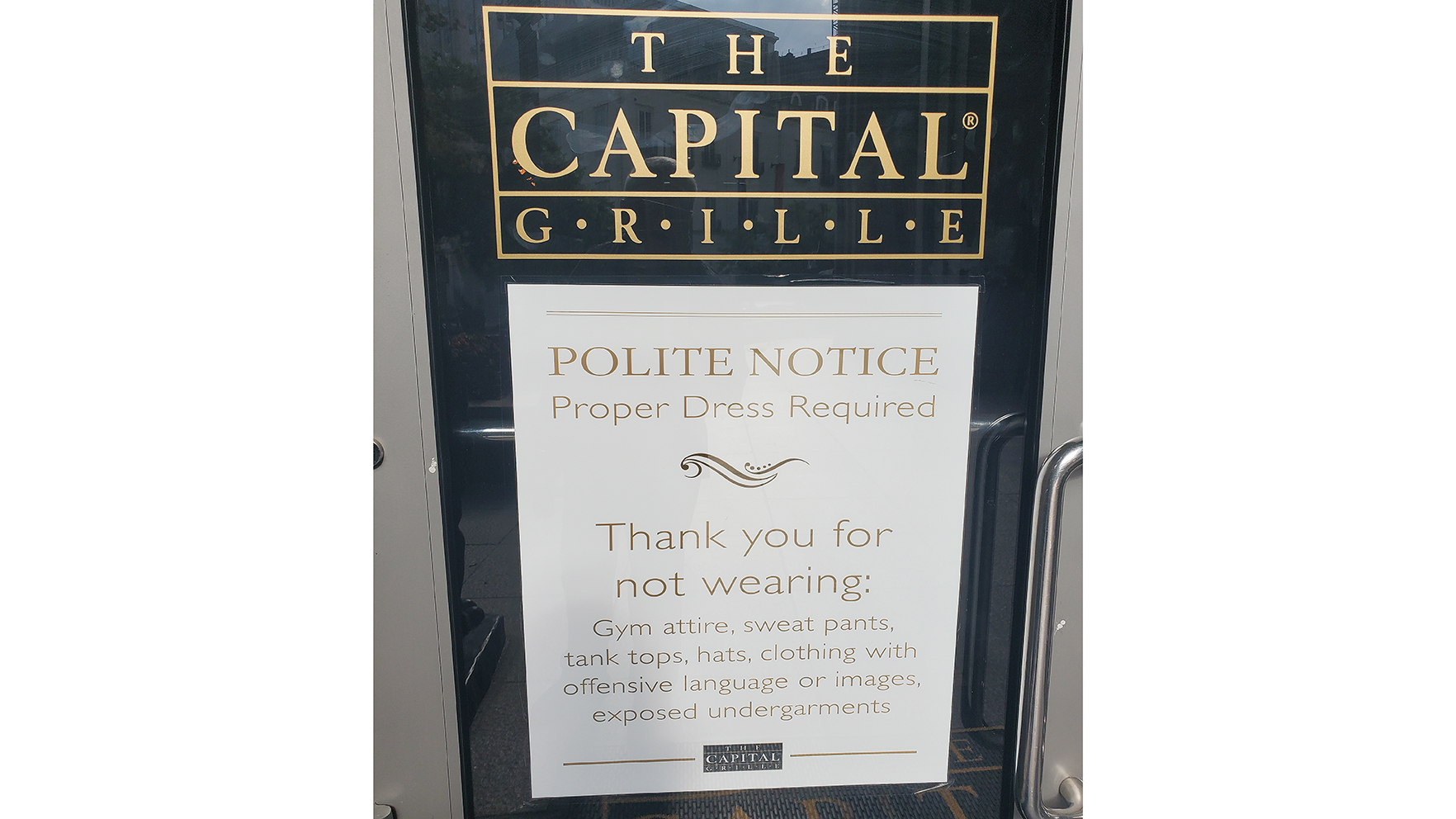

- IMAGE BY SEAN DIETRICH Shiloh Battlefield

There were ghosts everywhere. That’s what I kept thinking, while standing on Shiloh battlefield. Ghosts.

You could feel them. You could almost hear their fraternal laughter. You could smell their gunpowder.

A ghost is merely a soul who doesn’t want to be forgotten. Beneath our feet, at Shiloh National Military Park; beneath 163 years of gravel and grit, were tens of thousands of forgotten souls.

They were long forgotten boys in uniforms. Men who had families. Who never saw their wives again. Who nevermore kissed their mothers again, or shook hands with their old men, or bounced babies on their laps.

They were just children, really. Boys who once engaged in a great civil war, testing whether their nation, or any nation conceived and so dedicated, could long endure. Fighting for something they believed in.

My friend Bobby and I were playing music for a funeral directly on the battlefield. The funeral was held for the former National Park superintendent, Woody Harrell.

Woody was the man who made the Shiloh park great. A man who dedicated his life to preserving the sacred ground of the oft forgotten. A man who was recognized on the floor of the U.S. senate for his work here.

There were park rangers galore, attending the service. It looked like a ranger convention. Stetsons everywhere.

I met one ranger who looked like Teddy Roosevelt. He wore a table-flat brimmed hat and green suit, pressed sharply enough to slice tomatoes.

“McDougall’s brigade would have been fighting on this spot where we stand,” he said. “Would’ve been one heck of a fight on this ground.”

We weren’t all that far from Bloody Pond. A country pond where dying and wounded soldiers sought water during the battle. Wounded men would’ve crawled on their bellies toward the water.

The pond became the hub of death. The remains of young men lay in the shallows, eyes still open, staring at the heavens. Thirsty horses had collapsed and died in the water. So many men and horses drank from the pond that within hours the water was bloodred.

“Almost 24,000 died on this battlefield,” a ranger tells me. “And all these men want is to be remembered.”

Bobby and I played their music in memory of Woody. The music that belonged to these soldiers. The same hymns these men once sang during boyhood. Songs that once filled their little chapels back home in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, New York, Illinois, or New Hampshire.

I played fiddle for “Come Thou Fount,” and “How Firm a Foundation.” And as I bowed the strings, I was startled by something I saw. I almost dropped my fiddle.

It was in the middle distance. There beneath the trees stood a small brigade of uniformed soldiers from a bygone era. They were Federals and Confederates. Standing shoulder to shoulder in peace. Bearing arms. Bearing the flag. They looked tired, and ragged. Unshaven and gaunt. But young, and eternally frozen in youth.

I could see them, clear as glass. Erect, motionless, and at attention. I thought maybe I must be hallucinating.

I nudged a park ranger and whispered, “Can you see those soldiers?”

The ranger nodded. “Anyone can see them. Few will.”

Author, artist, columnist, storyteller, accordion player, musician and lover of Mayberry, peanuts and dogs Sean Dietrich is better known as Sean of the South. He can be reached through SeanDietrich.com.