Almost a year in jail, without an indictment

Published 10:28 pm Friday, August 24, 2018

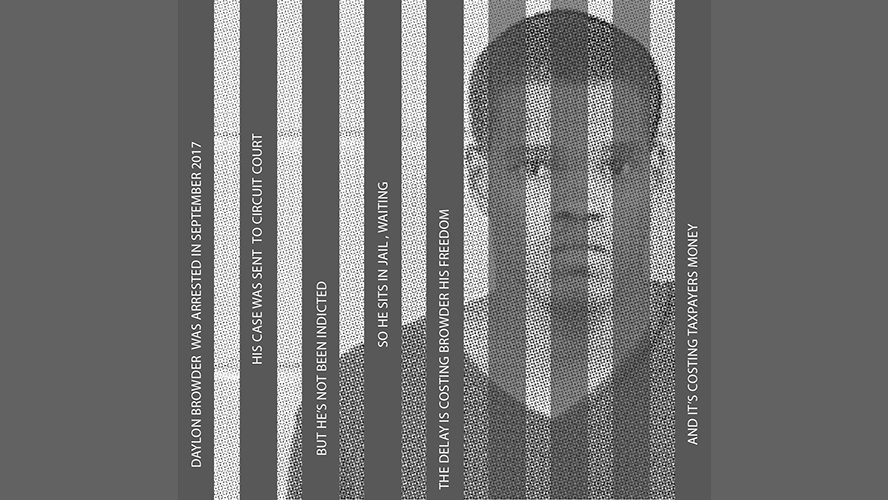

- Daylan Browder graphic

He was arrested on a Monday morning, last September, caught not quite in the act, but pretty close to it.

A jogger in Vernondale called the police when she saw a stranger opening the door of a vehicle belonging to a friend. It didn’t take long for the cops to patrol the area and find someone matching the description she gave them, and they pinched him then and there — he allegedly dropped a stolen gun and told them he’d broken into another vehicle on South First Street. They also charged him with a car burglary on Ellen Drive.

It would be easy to think Brookhaven police had 19-year-old Daylan Browder dead to rights, but his journey through the criminal justice system suggests otherwise.

As of today, Browder has been held in the Lincoln County Jail for 334 days without indictment. He was bound over to the grand jury at a preliminary hearing in Brookhaven City Court on Oct. 10 last year, but the district attorney, believing the Brookhaven Police Department’s case against Browder too weak to move forward, has not yet brought the charges up for that body’s consideration.

In six weeks, Browder will celebrate his second birthday behind bars, coming up fast on one year of incarceration without even having begun the process of a trial. He’s paying the price with his freedom, and taxpayers are paying the price with cash — as of Aug. 15, Browder’s stay in jail has cost more than $11,000.

“Once city court binds someone over the grand jury, they stop paying for that inmate and he becomes the responsibility of the county,” said Lincoln County Sheriff Steve Rushing. “We’re responsible for their clothing, food, medicine, dental work, doctor visits, mental health if they need it. We have to provide all that.”

The hand that feeds

The pretrial incarceration of Daylan Browder and other jail inmates scratching off days behind bars numbered in the hundreds is a growing problem that will cost county taxpayers an extra $137,000 in Fiscal Year 2019. Rushing asked the Lincoln County Board of Supervisors to bump up his jail budget by that amount earlier this month during a budget work session, saying the jail is housing more inmates for longer periods of time than ever before.

Next year’s budget for the jail will grow to $1.2 million, and according to the most recent jail census dated Aug. 15, the average length of stay of the 100 inmates is 130 days.

“I’m not putting down on anyone in the court system, but some of these costs are killer. I’ve got three down there now waiting almost a year to be indicted,” Rushing told supervisors on Aug. 20. “The longer they sit, the more it costs. If we ever want to get this jail cost situated from year to year, I’ve gotta have some help. There’s ways (the DA’s office) can help me cut down on those costs.”

Not all of it can be helped.

The longest-incarcerated inmate in the jail is 24-year-old Cordarryl Bell, who has been held on murder charges for 921 days since his arrest on Feb. 16, 2016. Bell’s trial resulted in a hung jury earlier this year and will be retried beginning Sept. 25.

Randy Smith has been inside for 608 days since his arrest for improper calls to 911 on Christmas Day 2016. His court records show orders for psychiatric evaluation and treatment, and he is currently stuck in jail waiting for a bed to come open at the Mississippi State Hospital, a hostage of the state’s historically-deficient mental health system.

Accused mass murderer Willie Cory Godbolt is up to 454 days, with a trial date inching closer while attorneys on both sides wait for completed autopsy reports from the underfunded, understaffed Mississippi Forensics Laboratory. So far, reports for six of the eight victims have been completed.

The other 97 inmates in the jail consist mainly of defendants working through the court process, jail trustys, state inmates sent down from the Mississippi Department of Corrections and recently-convicted defendants awaiting transfer to state correctional facilities. Incarceration costs for those inmates total $470,578, not counting others this fiscal year who have been transferred or released, nor other inmates who will be confined there before the fiscal year rollover on Oct. 1.

Lincoln County is responsible for them all. The county gets some help, but it isn’t always fair.

The City of Brookhaven reimburses the county $35 per day — the average daily cost for housing inmates — for defendants awaiting an appearance in city court, but just like in Browder’s case, that payment stops once the city court judge binds them over to a grand jury. City court can also sentence defendants to time in the county jail on misdemeanors, and the city picks up the tab for those stays. The county houses and pays for felonies.

Rushing said Brookhaven has thrown in $26,500 as of June 30. The figure is high this year, as the city averages around $18,500 in payments each year, he said.

MDOC also reimburses the jail for state inmates, but state law establishes the rate at $20 per day, forcing the county to eat the missing $15. The state system is unfair in other ways — the county is reimbursed for housing probation violators for 21 days, but once a judge makes the charges official, the state considers it the county’s problem and cuts off the money. Those inmates may sit in the jail for months on the county’s dime while the new charges are brought up.

Once a defendant is sentenced to state time, MDOC has 30 days to come pick them up. Until they do, the county pays.

“If you’re sentenced today, 99 percent of the time you’ll spend another 30 days here as a sentenced inmate,” Rushing said. “In that 30 days, it costs the county $1,000 — meanwhile, it costs the state $600. It’s a cost-saving measure for the state.”

Rushing said he’s working in his capacity as president of the Mississippi Sheriff’s Association to gather per-day costs from jails around the state — most average $30 to $35 per inmate per day — to present to the Legislature in hopes of a law change that will bring on more equitable reimbursement.

Good case, bad case, no case

But fairness on the balance sheet is only part of the problem.

While inmates like Bell, Godbolt and those sentenced and awaiting transport to prison are supposed to be kept secure in the county jail, Browder and others are behind bars in what Rushing called a gray area.

Every American has the Constitutional right to a speedy and fair trial, but in Mississippi speed is often slowed for the sake of investigation.

Robert Collins has been in the county jail for 327 days on armed robbery charges, and, like Browder, has not been indicted or brought before a judge in circuit court. Desmond Markham is charged with “multiple felonies,” and his stay in the jail is up to 142 days with no word from the grand jury.

Jesse Smith has been inside for 125 days on murder charges, Kenneth Graham is charged with possession of a weapon by a convicted felon and is up to 117. Andrew Rushing is on his 93rd day for possession of a stolen firearm with no indictment.

The county impanels two grand juries a year, and they meet for a few days every two months or so to determine if there is probable cause for a case to go forward. There have been plenty of opportunities for Lincoln County District Attorney Dee Bates to present these cases to the grand jury for indictment, but he has not done so.

“We do not go to the grand jury until we have a completed file,” Bates said. “That way you can tell the grand jury everything — and they need to know everything. The grand jury is not just a rubber stamp. We tell them all the evidence the state has, and what it’s lacking.”

Bates said his office reviews the file on every defendant before presentation to the grand jury and returns those lacking evidence to the arresting agency for more work. It makes for best practices for the district attorney’s office, but can leave defendants parked in the jailhouse.

Bates said his frustration was growing on the Browder case. He said he has sent investigators from his office to help the Brookhaven Police Department interview witnesses to the year-old charges, and has only recently placed Browder on the docket for the grand jury’s consideration after pushing for enough evidence and statements to make it worthwhile.

“The DA’s office should not be doing police work, but I gotta make it happen,” Bates said. “There are Constitutional rights (Browder) has, and I have an obligation to protect them. (We’re investigating because) I owe an obligation to the victims, also. ”

Browder and the other inmates at or over the 100-day mark without indictment were all arrested by the Brookhaven Police Department. Brookhaven Police Chief Kenneth Collins did not immediately return messages seeking comment for this story.

Let my people go

Back in March, Lincoln County Circuit Judge Mike Taylor appointed Browder a public defender, who successfully argued his bond down from $100,000 to $25,000.

Taking up inmates’ cases before they actually have cases is a new practice in Mississippi, mandated last year by the Mississippi Supreme Court’s “Mississippi Rules of Criminal Procedure,” which set new guidelines on bail amounts and access to legal counsel.

The rules are meant to stop the state’s historical practice of allowing inmates like Browder, whose indictments are a long time coming, to languish in jail under high bonds, with no legal help, while law enforcement and prosecutors ponder their cases.

The new rules ensure the right to see a judge within 48 hours after an arrest, and requires judges to release those deemed not a flight risk on a written promise to appear for court or pay fines. County sheriffs are now required to publish a monthly jail census that is reviewed by a judge, who ensures inmates inside more than 90 days have access to a lawyer.

“Judges are required to review those lists, and they should demand explanations as to why cases are not moving forward,” said Cliff Johnson, an assistant professor at the University of Mississippi School of Law and director of the school’s MacArthur Justice Center. “We are of the view that, absent extraordinary circumstances, judges should release pretrial detainees who are unable to make bail and have not been indicted within 90 days of arrest.”

Before last summer’s new rules, inmates in county jails often sat months or years between preliminary hearings and indictments, unable to afford high bonds and without legal help to get them lowered — a jail inmate does not have a public defender until a judge appoints one, and under the old system, an inmate would not come before a judge until after being indicted.

Johnson’s MacArthur Justice Center has worked to make sure the new rules are enforced. Earlier this summer, the center and the American Civil Liberties Union settled a lawsuit against Scott County on behalf of two inmates there who had been held for eight and 10 months, respectively, without having been indicted or appointed an attorney.

The settlement requires the whole Eighth Circuit Court District — Leake, Neshoba, Newton and Scott counties — to hire a chief public defender who will assign attorneys to defendants upon arrest.

Enforcement of the rules has required lawsuits because of the political pressure felt by elected sheriffs, judges and district attorneys, who serve conservative electorates that demand punishment and rarely worry about the technicalities it takes to get it, or the rights of the accused. Some judges are reluctant to release non-indicted inmates, and some district attornies are reluctant to give up on bad cases.

“It is unacceptable for American citizens, including residents of Lincoln County and Brookhaven, to be held for months on end without formal charges and without counsel,” Johnson said. “The Constitution of the United States and the Mississippi Rules of Criminal Procedure make clear that money bail may be imposed only if a judge finds that a person is a flight risk or poses a danger to the community. The law also requires Lincoln County and the City of Brookhaven to appoint counsel for indigent defendants within 48 hours of arrest, and a lawyer must represent the client throughout the period of pretrial detention and fight for the client’s release. If Lincoln County and the City of Brookhaven are failing to live up to these obligations, its citizens should demand reform. Otherwise, the county and the city are vulnerable to costly litigation that they likely will lose.”

Adjustment

Brookhaven attorney Will Allen, who represents the Mississippi Sheriff’s Association, hopes jail costs begin to decrease as the state’s criminal justice system conforms to the new rules. His main concerns are his sheriffs, who are not responsible for making sure inmates’ court proceedings move along, or that they are appointed attorneys or fair bonds.

The sheriffs have two jobs — make sure inmates appear for trial, and eat the costs of housing them.

“Mississippi’s sheriffs have found the new criminal rules helpful in moving detainees out of their jails,” Allen said. “Continuing to detain individuals is costly to the county and the sole reason to hold pretrial detainees is to assure their appearance at trial. The association has high hopes the new criminal rules will continue to be properly implemented and our pretrial detainee jail populations will decline.”