‘The Factory’ was a cut above the rest

Published 7:30 pm Saturday, October 29, 2016

Most old timers in Lincoln County can tell tales of “The Factory.”

If you didn’t work at Stahl-Urban yourself, you knew somebody who did.

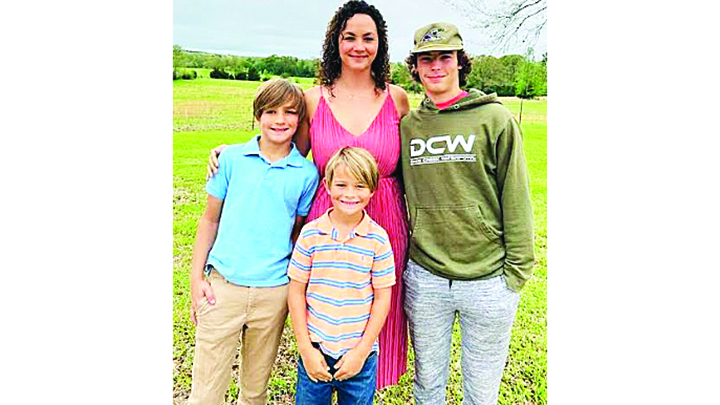

Photo by Donna Campbell/Yvonne Wooten was a young bride when she bought her first living room suite with the money she earned sewing sleeves at the Stahl-Urban garment factory 64 years ago. She used this pair of scissors to cut her thread then, and later to make clothes for her daughters and grandchildren. She’s wearing the apron she made herself out of two dairy feed sacks, to keep the lint and thread pieces off her clothes when she was on the assembly line.

“Just about everyone who is from Lincoln County has had a family member work at the factory,” said Tammie Santos Brewer, a board member with the Lincoln County Historical and Genealogical Society said. Brewer, who lives in Pearlhaven near the old, empty building, comes from a line of three generations of women who worked there. Her great-grandmother, grandmother and mother all earned Stahl-Urban paychecks at one time or another.

Trending

The garment manufacturing factory was located in Terre Haute, Indiana, in the early 1930s, but became a victim of unionize workers and its owners had to decide whether to hire nonunion workers or move their production to Brookhaven.

They chose the latter and reopened their factory in 1936.

Between 1940 and 1945, Stahl-Urban produced 1.5 million uniforms for the military, which constituted nearly all of its production. By 1963 the former work clothes maker had switched to men’s and boy’s outerwear, including pants, shirts and jackets.

The historical society hosted a program last week with Stahl-Urban historian Keith Reeves as the speaker. Reeves’ mother and aunt, Stella West Reeves and Louise West, were brought to Brookhaven from Indiana to train the new factory workers.

About 50 people attended the meeting at the Jimmy Furlow Senior Citizen Center to share stories about the factory and the impact it had on their families’ lives. Among them was Yvonne Wooten, of East Lincoln, and her daughters, Dianne Altman, of East Lincoln, and Linda Wooten, who lives in Alabama.

Wooten’s job at Stahl-Urban was her first.

Trending

Now 80, she recalls being 17 and married for two and a half years, living with her parents. She wanted them to get their own place. She wanted to pick out furniture and make a home so they could start a family.

“I wanted a living room suite and my husband said, ‘Well, go to work,’” she said. “Go to work meant ‘The Factory’ because that’s all there was.”

When Wooten’s baby girl Dianne was just six weeks old, she got that job.

Her mother, Deloris Thames, was already a Stahl-Urban seamstress and pulled some strings to get her hired, too.

Wooten wasn’t a sewer. “I took home ec in school school but that was the only thing. You had to make an apron or maybe a skirt but that was it,” she said.

But the young woman was determined she’d make a better life for her little family one stitch at a time. A neighbor kept Dianne and Wooten worked.

Reeves and West trained her to sew on an assembly line and ordered her a pair of Clauss scissors, which she had to pay for. She thinks they were about $15 to $20, which was more than a day’s pay in 1952.

She was a quick learner.

She was assigned a place on the line and her own machine. She sewed sleeves together for the poplin jackets her section produced. Seven hours a day, five days a week, for almost six years, she sewed sleeves.

Most of her co-workers were women, although a few men worked there too. They mostly had more labor-intensive jobs like maintenance, though.

The women didn’t talk to each other much, focusing on the stitches and keeping the pace, but every once in a while she’d get to shoot the breeze with the woman next to her as she waited for the jacket pieces to make their way down the line to her station.

She never cried at work, but she did put some blood and sweat in her job. Literally. Wooten can’t count how many times she sewed her finger to the sleeves as she fed fabric through the machine.

She made about $75 a week, which was the average for a worker in ’52. “The faster you were the more money you made because you could do more pieces if you were fast, but it had to be good, excellent work. You couldn’t just slap them together,” she said.

Wooten and many like her carpooled to the factory each day. Living in Topisaw, she rode with Charles McGraw who’d bought a truck to transport other folks in the community to Brookhaven to work. Wooten’s father built a camper to give them shade, and McGraw added benches.

Working at Stahl-Urban had other perks, she said.

Because she was a Stahl-Urban employee, she was able to get credit. A living room suit was the first thing she bought.

She picked it out from R.A. Doerr Furniture Store. “It was big long, extra long couch that made out into a bed and it had one chair that went with it and it had two of the most beautiful lamps and two throw rugs,” she said, smiling at the memory more than 60 years later. “I was just tickled to death.”

Besides her memories of the factory, Wooten still has her scissors. She’s also got her mother’s pair, which were slightly bigger and heavier.

Altman inherited her great aunt Maggie Townsend’s pair. Townsend worked there until it closed in the mid-80s.

Wooten is sentimental about her scissors, which she continued to use after leaving the factory. As an accomplished seamstress, she used those scissors to make clothes for her children.

“They were the best scissors you could buy,” she said.

“ You didn’t dare use those scissors to cut paper or cardboard,” Altman said and her sister nodded in agreement.

After her years at the factory, Wooten went to beauty school — and learned to use a different type of scissors — then opened a beauty shop.

She ran Yvonne’s for almost 50 years. “The sign is still there in the front yard but she doesn’t take customers anymore,” Altman said.

She also worked another assembly line job, making condensers at Potter Co. in Wesson.

Wooten values her time at Stahl-Urban and the work ethic she learned. She said the company is an important part of Lincoln County’s and Brookhaven’s history.

“Back then, most women weren’t trained to do anything. They’d been at home,” she said. “So when they went to work at the factory, that was a blessing because it brought in more income.”

Once a year, workers were paid with a sack of silver dollars instead of a paper check. It was a marketing ploy to show the community the economic benefits the factory provided to the town.

On that annual payday, businesses were flooded with the coins.

“They were glad to get them,” Wooten said.