‘Well, I’d like to read your meters’ — Bogue Chitto loves its old meter man

Published 10:54 pm Friday, January 19, 2018

The history is in him. He has lived it, made a little himself.

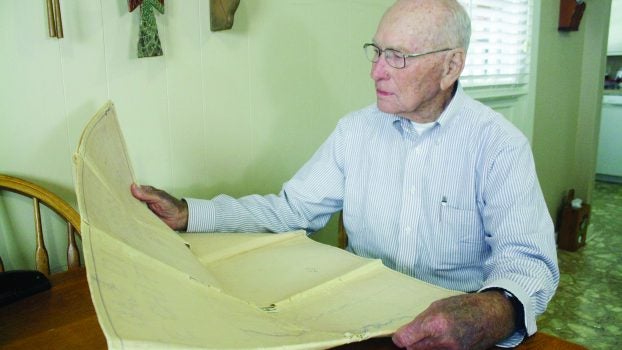

Bogue Chitto’s Henry Carlisle, 89, surrounds himself with history’s comfort, as old men do.

In his home are sepia portraits of forebears, model cars, heirlooms in the hutch. Black and white Polaroids of himself in uniform, young and straight, tattered maps and typed genealogy.

Nativities and poinsettias and little trees celebrate the season. Painted crosses, a single-page copy of “It Is Well with My Soul” tacked on a blue board. These belonged to the woman who was his for 62 years, until last February.

The family Bible is laid out and open, the word of God in large print for old eyes.

I remember the days of old;

I meditate on all thy works

I muse on the work of thy hands.

Psalm 143:5

Rocking slow in a cushioned glider, Henry muses on where the Hands have led him.

He calls up fathers and friends and mentors, long in the grave. Schoolhouses gone and growed up. Landmarks knocked down and built over. He closes his eyes when he needs to remember.

His spotted hands once picked cotton, split wood, yanked peanuts from the dirt. He’s driven a pulpwood truck and a taxicab. He’s built lawnmowers, managed warehouses. He’s seen the atom split, and fire in paradise.

If you’re on natural gas in Bogue Chitto, he’s seen your meter.

Not all folks know Henry, National Association of Atomic Veterans member. They all know Henry the meter man, who walked up to a pipe-laying site at Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church in 1998 and talked himself into a job.

“I said, ‘Well, I’d like to read your meters.’ I just wanted something to do,” Henry said. “Turns out the Public Service Commission wrote him a letter saying he had to have someone who could be in Bogue Chitto in 30 minutes. He said, ‘Well, I might hire you.’”

He’d been retired for seven years. He was 70. A man like Henry can only sit around so much. He was hired.

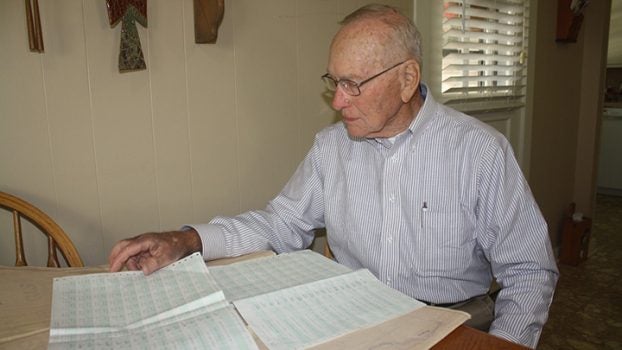

For the next 16 years, Henry checked every Mississippi River Gas, LLC meter in Bogue Chitto (it was Mississippi Gas Corp. back then). Every month, he’d take a spreadsheet and a pen and visit all 180 connections — the school, the lodge, the lawyer’s office, households.

He’d start at the meter station on Bogue Chitto Road. Read his way into town and out to the truck stop. Back down Highway 51 to end at the church. He’d take his readings home and fax them in.

Henry didn’t have a company truck. Not even a uniform. Nobody got scared when an old man walked on their land and started taking notes, anyway.

“Everybody just about knew me by that time,” he said.

Of course they did. By then, Henry had been in Bogue Chitto 30 years. He’d been in Lincoln County all his life.

He was born at home in Fair River, March 5, 1928, the fourth of nine raised by Walter and Suzie Ritchie Carlisle. His daddy worked as a boiler man at Pennington’s sawmill, back when steam powered the bands. His mother raised the babies and put them to work.

Growing up in Lincoln County in the 1930s meant chopping wood every day. Building fires in the fireplace and the wood stove every morning. Drawing water from a well.

Every evening he and his brothers and sisters milked a cow named April. When the season was late, they cut down corn and sugarcane, dug up peanuts and dried them on the roof. Yellow jackets swarmed them when they cooked cane syrup.

They hammered out plow points over burning coals and plowed behind a team of mules. When panthers hollered from down in the woods, the mules got scared and wouldn’t pull.

In August and September, the school at Fair Oak Springs sent everyone home after half a day to pick cotton.

“Just about everything we ate, we raised,” Henry said. “Most of what we bought was flour. I guess we bought sugar, too.”

When he got older, Henry drove a Ford pulpwood truck with no cab, just a windshield, and a dead battery. When the Carlisles came to Brookhaven, they parked on a hill near First Baptist Church so they could roll it off to get home. His senior year of high school, he drove a school bus to make a little extra.

“Money was hard to get back then,” he said.

After he graduated in 1947, Henry worked in the parts department at Boling Motors, where the Piggly Wiggly on Monticello Street sits today. He sold parts through a window and washed the Dodges on the lot every morning.

Later that year he drove a taxicab for Bob Leary.

“A lot of people didn’t have cars back then,” Henry said. “We’d go get people and take them to work, drive them home in the afternoons.”

There wasn’t much future in driving cabs. In 1948, Henry and his friends, Cecil Dow and Vernon Ray Smith, joined the U.S. Air Force.

He’d always thought about the sky. He remembers planes flying over when he and his brothers were plowing fields. They’d stop the mules a minute and watch the craft cut the sky, and disappear.

“I told my brother, ‘One of these days I’m going to fly in an airplane where it’s cool,’” Henry said. “In ’48 they were still drafting people to go in the Army, and we didn’t want to go in the Army. So we volunteered for the Air Force.”

Henry went through orientation in Hattiesburg. Thirteen weeks of basic at Sheppard Air Force Base in Witchita Falls, Texas. A year of flight mechanic school at Chanute AFB in Illinois.

“We had to strip engines down all the way, and put them back together,” he said. “Man, they had 1,000 parts.”

After he was trained up, Henry was sent to Eglin AFB, where the Air Force did pioneering work in the development of remotely piloted aircraft. He served as flight engineer on B-17 Flying Fortress.

It was a drone. He kept the engines going. The pilot followed along in another airplane.

“We’d start the aircraft up and be sitting there, and all of a sudden the throttles would start moving and we’d start rolling down the runway,” Henry said. “We had pilots, but they didn’t fly the plane. Unless something went wrong.”

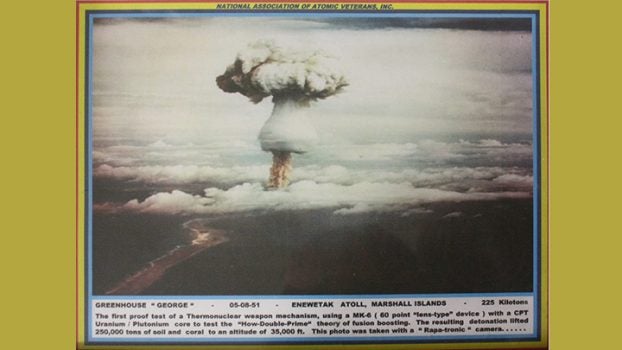

Henry liked that Eglin was only 300 miles from Lincoln County. But in 1951 the Air Force moved him again, 7,000 miles away. He spent 10 months flying in observations planes at Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands as part of Operation Greenhouse, a series of four nuclear tests that led to the nation’s first thermonuclear weapons.

“We had to wash the planes down to get the radiation off. We had a five-gallon bucket of Tide,” Carlisle said. “Then we’d have to take a dozen showers and they’d come around and check us with a Geiger counter to make sure we didn’t have none on us.”

In 1952, Henry moved again, to Naval Air Station Point Mugu in California. He spent six months there on a joint program to develop guided missiles. Henry’s work laid the foundation for the development of the premier weapons of the Vietnam era — the AIM-7 Sparrow and AIM-54 Phoenix air-to-air missiles.

By then, Henry was ready to go home. His four-year enlistment was over.

“I think I would have signed up but some of the men were getting sent to Alaska and Korea. I decided I didn’t want to go to either one,” he said.

Henry came back to Lincoln County. He worked at the Stahl-Urban plant, then got a job driving a cement truck to local oil wells for Halliburton.

In 1954, a friend introduced him to Dorothy Wallace. Her daddy, Esco Wallace, was a railroad man in McComb. She worked at the telephone office. Henry liked her. He courted her six months and married her on Oct. 15.

“I guess I got tired of being single,” he said.

Halliburton promoted Henry, so he and “Dot” moved to Laurel for the next dozen years. They had a daughter, Cindy, in 1956. Mike was born in 1958.

Dot wanted to go back home, so in 1967 they rented a house in Brookhaven and Henry went to work for St. Regis Paper Company in Monticello. It later became Champion International. Now it’s called Georgia-Pacific.

In 1968, they bought their home on Fox Road in Norfield from Tom Moak. Henry stayed with the paper mill for 23 years. He retired as shipping foreman in 1991.

“I guess I was just getting old enough to stay put,” he said.

After retirement, Henry fished. He hunted. He went to church. He became a big supporter of Bogue Chitto basketball. But the same restlessness that made him drive cabs and build lawn mowers made him read meters.

He’s still restless today. It keeps him young. He plans veterans’ get-togethers, church meetings and doctor visits on a calendar in the kitchen. There’s something every day. He’s a scheduled man.

Last year was hard on Henry. Dorothy passed away in the nursing home on Feb. 10. Now he’s by himself in a big house.

But he’s not really alone.

Mississippi Democratic Party Chairman Bobby Moak was friends with Henry’s son, Mike. They were friends since elementary school and roommates at Ole Miss.

Moak says he spent as much time on the Carlisles’ couch as he did his own growing up, and as an adult looked forward to seeing Henry stop by his law office while making the monthly meter rounds.

“Henry would come in and say, ‘Hey Bobby, you owe this much money on ‘yo meter.’ And I would be like, ‘Ladies, please cut Henry a check so he won’t disrupt my service,’” Moak said. “He’s just a very special person to me.”

Annette Reeves was a teenager at Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church when the Carlisles moved to town. Her momma let her go on a camping trip with the new family. Henry and Dot cooked bacon and eggs over a fire for breakfast.

It was Sunday, so they had church in the woods.

“Henry led us down to the creek and we had one of the most special services I’ve ever been in,” Reeves said. “We sang the old hymnals like they used to sing. We were sitting on logs and Henry was standing up. He did a full service and I cried like a baby.”

Marsha McCaffrey graduated from Bogue Chitto in 1995. She played basketball for the Lady Bobcats and remembers Henry and Dot at every game.

“They sat in their own kind of designated seats. They should have been labeled,” she said. “If you were from Bogue Chitto you knew not to sit there because that was Mr. Henry’s and Mrs. Dot’s seats.”

Basketball wasn’t just a phase. Lincoln County School District Superintendent Mickey Myers learned how to administer schools at Bogue Chitto Attendance Center, where Henry’s granddaughter, Christi Terrell, coaches the Lady Bobcats basketball team.

“When Bogue Chitto won the state championship in 2016, he and Mrs. Dot were in the big house,” Myers said. “He’s an avid supporter of our school and our community. The epitome of a southern gentleman.”